Does Excess Mulch Depth Lead to Poor Tree Growth and Condition, Root Girdling, and Decay? A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

Mulch is placed around the base of trees to improve soil conditions, water conservation, and tree growth while decreasing weed competition, mower damage, and soil compaction. Current industry best practices and trade magazine articles recommend a mulch depth of 5 to 10 cm (2 to 4 inches) and caution against exceeding this depth, warning of issues affecting stem tissue like stem girdling roots and pathogens. To examine scientific support for this threshold, we conducted a systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature on excess mulch depth. We identified 11 studies that examined the effects of increasing depths of mulch on tree and soil physiology. All but two studies tested mulch depths exceeding the 5- to 10-cm (2- to 4-inch) range. The impact of deep mulch is unclear; methodological differences, including mulch type and examined variables, limit comparisons between studies. It is possible that fine mulch with low porosity results in deleterious effects similar to planting trees too deeply, explaining observations by practitioners. While further research should determine the effects of mulch depth beyond 10 cm (4 inches) on tree physiology, there are often negative side effects reported for exceeding 10 cm (4 inches) but few negative effects reported for mulch depths within 5 to 10 cm (2 to 4 inches).

Introduction

Applying a layer of mulch around the base of a tree prevents or reduces many of the common abiotic disturbances that impact trees in the urban environment. Mulch can improve soil moisture, reduce soil erosion and compaction, prevent soil temperature fluctuations, increase soil nutrition, decrease weed competition, and decrease the impact of salts and environmental contaminants (Chalker-Scott 2007; Marble et al. 2015; Saha et al. 2020). A ring of mulch around the base of a tree also helps to protect it from mechanical damage caused by mowers and grass or string trimmers (Morgenroth et al. 2015; Blair et al. 2019; Lilly et al. 2022). When managing trees through construction, proactively applying a layer of mulch can reduce soil compaction caused by the movement of heavy equipment (Lichter and Lindsey 1994; Fite et al. 2011). All these benefits of mulch contribute to improved tree establishment and growth (Chalker-Scott 2007; Maggard et al. 2012).

Despite these many benefits, excessive mulching may cause problems. Within the arboriculture industry, there has been significant emphasis in trade magazines and extension publications on the negative impacts of excessive mulch depth, including stem girdling roots, early tree mortality, excessive temperatures, and reduced gas exchange (Billeaud and Zajicek 1989b; Rakow 1992; Ball 1999; Herms et al. 2001; Carlson 2002; Jackson 2018; Smith 2020; Boggs 2024). These problems were noted in unsubstantiated articles in trade magazines as early as the 1980s when Gouin (1983, 1986) wrote that over-mulching—both excess mulch depth and mulch against the trunk—allegedly caused the suffocation of shallow roots, the decomposition of roots, the production of roots from the trunk, the formation of trunk cankers, and created environments conducive to pathogens like Phytophthora cinnamomi (cinnamon fungus) and Botryosphaeria ribis. These cumulative impacts were said to produce symptoms like foliar chlorosis, small leaves, poor growth, and dieback (Gouin 1986). Gouin (1986) wrote that “often the problems are irreversible, and the plants are doomed.” These sentiments have been echoed in trade articles (e.g., Ball 1999; Carlson 2002), extension fact sheets (e.g., Boggs 2020; Appleton 2021; Rainey et al. 2022; Boggs 2024), and online resources (e.g., Johnson et al. 2008) ever since.

Because trade magazines and extension publications serve as important methods of knowledge transfer for arborists (Martin et al. 2024), the sentiment that too much mulch is deleterious has been widely accepted, despite commonly lacking reference to formal peer-reviewed and replicable research (Giblin 2013). Presently, industry best management practices (BMPs) suggest a layer of 5 to 10 cm (2 to 4 inches) of mulch applied around the tree but kept away from the trunk (Herms et al. 2001; Watson 2014a; Costello et al. 2017). After settling, the mulch should be 5 to 7.5 cm (2 to 3 inches) deep (Watson and Himelick 2013; Watson 2014a).

The recommendation for a shallow depth of mulch must be balanced against the needed depth to achieve desired outcomes. Some of the many benefits of mulch, including weed control and construction damage mitigation, are dependent upon a mulch depth that exceeds the BMP’s 5 to 10 cm (2 to 4 inch) depth recommendation. For example, Greenly and Rakow (1995) found that increased mulch depth, which they tested up to 25.5 cm (10 inches), reduces weed density and diversity. In another example, Lichter and Lindsey (1994) recommended a mulch layer of 15 cm (6 inches) or greater to reduce soil compaction during construction. Presently, it is unclear what scientific evidence supports the standard 5 to 10 cm (2 to 4 inch) mulch depth recommendation nor what should be considered an excessive mulch depth for routine applications.

To better understand the negative impacts on tree physiology associated with mulching in excess of the 5 to 10 cm (2 to 4 in) depth currently recommended in industry BMPs and textbooks, we conducted a systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature. These types of “mini reviews” that focus on specific research questions are increasingly common, summarizing nascent literature on commonly held practices that may lack scholarly support and providing straight-forward summaries for practitioners (Elfar 2014). In environmental sciences, mini reviews have examined limited literature on emergent topics like biochar in agriculture (Wang et al. 2022), green nanotechnology (Salem 2023), wastewater bioremediation (Nyika and Dinka 2022), plastic marine debris (Wayman and Niemann 2021), social sciences in dry forest restoration (Powers 2022), and the impact of nitrogen emissions on environmental and human health (de Vries 2021). This format is important in arboriculture where many practices and commonly held perceptions lack scientific review (Gillman 2008; Chalker-Scott and Downer 2020).

In this systematic mini review of mulch depth, we examined the methods, tested depths, overall findings, and limitations of studies on the impact of mulch depth on tree physiology. This review benefits arborists, horticulturists, and landscapers by providing a summary of evidence supporting—or contrasting—their understanding of deep mulch applications. This review is also beneficial for professional associations like the International Society of Arboriculture (ISA), which produce BMPs and standards that reflect both industry consensus and the known science. For researchers interested in tree physiology and interactions with physical, chemical, and biological processes of soils, this review highlights research gaps and the opportunity for future research.

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy and Screening

This review was conducted according to the procedures for systematic reviews outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)(Page et al. 2021b). First, a search was conducted in 5 common databases for keywords in study titles, abstracts, and keywords (Figure 1). The search terms and strings with Boolean operators were: “mulch” AND (“depth” OR “volcano” OR “girdling” OR “rot” OR “decay” OR “insect” OR “pathogen” OR “pest” OR “rodent”) AND “tree.” Akin to Martin and Conway (2025), we also searched the 10 arboriculture and urban forestry journals that are most often referenced by arborists and urban foresters (Martin et al. 2024) as several are not indexed in the 5 databases (Hauer and Koeser 2018). In addition to the 5 databases and 10 arboriculture and urban forestry journals, we also searched the Journal of Environmental Horticulture. Any researcher funded through the Horticulture Research Institute Grant is required to be published in the Journal of Environmental Horticulture (Horticultural Research Institute [date unknown]), so it was likely that mulch depth studies have been published in this venue. The search of the databases and first 10 journals was conducted on 2024 December 12. We updated the review to include the Journal of Environmental Horticulture on 2025 March 19.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram of the systematic literature review for studies on the effect of mulch depth on tree physiology (Page et al. 2021a). Journals marked with an asterisk (*) did not offer .ris export options for search results; therefore, study records were manually compiled into a .ris file and uploaded to Covidence.

A total of 1,200 studies were identified from the databases and journals (Figure 1). All studies identified during the search were imported into Covidence, a systematic review platform, that was used for study screening. After the removal of duplicates, 1,055 studies were screened based on titles and abstracts. Following screening, 89 studies were read in full to assess their eligibility for inclusion.

Only English-language studies were included in this review. To be included, studies must have examined trees or woody shrubs and considered mulch depth as a factor. At least one type of mulch used must have been a woody mulch type. Mulch depth must have been varied in the study design. Therefore, studies that compared no mulch (control) to one depth of mulch (e.g., 10 cm) were excluded. If studies had multiple experiments, the study was included if at least one experiment met the inclusion criteria, in which case the relevant experiment is examined in the Results. To ensure that studies of high-quality were included, articles published in non-peer-reviewed journals (e.g., Arborist News) were excluded. No automated filters were used to exclude studies based on these criteria.

After 10 studies were determined to be eligible for inclusion, the included studies were read to identify any additional studies cited in the included study that meet the inclusion criteria, a literature review process called backward citation searching (Jalali and Wohlin 2012). Through backward citation searching, we identified one study that met the inclusion criteria and was therefore included as the 11th study in our review (Pellett and Heleba 1995)

Analysis of Included Articles

For each study, we identified bibliographic details (publication year and journal), study methods (mulch type and depth and tree species tested), and the variables examined. Because some species can be classified as trees or woody shrubs, the term “tree” is used throughout to avoid differentiation between woody shrubs and trees. Several studies included multiple experiments. Only the experiments that met the inclusion criteria were examined. We present an overview of the findings of the 11 studies and examine their limitations.

Results

A total of 11 studies were identified that examined the impacts of mulch depth on tree physiology. The 11 studies are identified in the Appendix. The publication dates ranged from 1989 to 2023, although 9 studies were published before 2010. Only two journals had published more than one study. In the Journal of Environmental Horticulture, 5 studies were published, and 3 studies were published in the Journal of Arboriculture—now publishing under the name Arboriculture & Urban Forestry.

Mulch Depths and Types

All but two studies—Bartley et al. (2016) and Richardson et al. (2008)—tested woody mulch depths that exceed the 5 to 10 cm (2 to 4 inches) recommendation for normal mulch depths by at least 5 cm (2 inches) (Figure 2). All studies included a control depth—that is, an area of no mulch (0-cm [0-inch] mulch depth). Excluding the no-mulch control depth, 4 studies tested 2 mulch depths while 7 studies tested 3 mulch depths. The most common interval between tested depths was 5 cm (2 inches)(n = 8), followed by 10 cm (4 inches)(n = 5), and 7.5 cm (3 inches)(n = 4). Only two studies, Greenly and Rakow (1995) and Sun et al. (2023), tested mulch depths with inconsistent intervals.

Figure 2.

Mulch depths tested in the 11 reviewed studies.

Studies varied in how many mulch types were examined. There were 5 studies that only tested 1 mulch type and 3 tested 2 mulch types. Beyond 2 mulch types, Billeaud and Zajicek (1989a) tested 4 mulch types while Foshee et al. (1996) and Bartley et al. (2016) tested 5 mulch types. This totals to 25 mulch tests across 11 studies and 17 unique mulch types. Of the 17 unique mulch types, only 3 were used in more than one study: pine (Pinus spp.) bark nuggets (n = 5), pine (Pinus spp.) wood and bark mulch (n = 4), and hardwood mulch (n = 2).

Tested mulches were made from 12 different source materials, including 7 tree genera and species. Across the 25 mulch tests, pine (Pinus spp.) was the most commonly used mulch material, used in 10 studies. This includes the pine species loblolly pine (Pinus taeda). The other tree genera and species used as mulch material—baldcypress (Taxodium distichum), cypress (Cupressus spp.), eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana), pecan (Carya illinoinensis), Chinese privet (Ligustrum sinense), and sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua)—were each only used once. There were 3 studies that used undefined wood mulch, classifying it as hardwood mulch (n = 2), softwood mulch (n = 1), chipped limbs (n = 1), and shredded mulch (n = 1). Grass clippings, garden waste, hardwood leaves, and newspaper were each used once.

Tree Species

After updating botanical names to reflect current nomenclature per Royal Botanic Gardens‚ Kew (2024), a total of 22 species were used across the 11 studies. In examining the impact of mulch depth, 6 studies tested only 1 tree species and 3 studies tested 2 tree species. Of the 3 studies that tested more than 2 tree species, Pellett and Heleba (1995) tested 3 species, Richardson et al. (2008) tested 4 tree species, and Hild and Morgan (1993) tested 5 tree species. Wax-leaf/Japanese privet (Ligustrum japonicum) was the only species to appear in more than one study.

Replicants and Plot Designs

The total number of trees planted in any study varied between 49 and 400 trees (Table 1). Six studies tested multiple tree species and reported the number of trees. Greenly and Rakow (1995), Hild and Morgan (1993), Richardson et al. (2008), and Bartley et al. (2016) used the same number of tree species per treatment whereas Arnold et al. (2005) and Pellett and Heleba (1995) used different numbers of tree species per treatment.

Table 1.

Number of trees, treatments, and replicants and block design used in the 11 reviewed studies on mulch depth.

Plot designs were most often randomized complete block design where each tree was an individual unit planted into the block (n = 5)(Table 1). In two studies, a randomized complete design was used with trees in individual nursery containers. Split-split plots, split plots, random plots within a forest, and randomized complete block design with 7-m2 plots were all used in one study each.

In 2 cases, the total number of trees did not match the number of replicants and blocks. In Greenly and Rakow (1995), a total of 60 trees, divided between 30 Quercus palustris and 30 Pinus strobus, were planted in 4 blocks with an equal number of Q. palustris and P. strobus per 3 mulch depths and two mulch types plus one unmulched control per block. With 7 treatments per species (6 mulch treatments plus 1 control) replicated across 4 blocks, that would total 28 trees per species; whether the 2 remaining trees per species were kept in reserve was not mentioned. Arnold et al. (2005) described having 8 blocks of Koelreuteria bipinnata with “single plant replication of each treatment combination” and 12 treatments (4 mulch depths, 3 planting depths). This would total 96 K. bipinnata, 12 greater than the 84 trees mentioned earlier in their study.

Variables Examined

The 11 studies explored variables grouped as tree physiology, soils, and pests (Table 2). Within these 3 broad groupings, variables were classified into 9 tree physiology classes, 7 soil classes, and 2 pest classes. Tree physiology classes were the most common, of which trunk diameter and area was most commonly measured (n = 6).

Table 2.

Classification of variables measured by the 11 reviewed studies. Open circles indicate variables included in authors’ own indices. Totals for each class include only the filled black circles.

Methods for measuring variables within these classes varied. For example, trunk diameter was measured at just above the root flare by Greenly and Rakow (1995), at 1.3 cm (0.5 inches) above ground level by Hild and Morgan (1993), and at 15 cm (6 inches) above the soil surface by Arnold et al. (2005). In another example, tree condition was measured using a scale of 0 (very poor quality) to 5 (“high quality container plant with excellent color and aesthetic appearance”) by Billeaud and Zajicek (1989a) and a 0 (no observed injury) to 10 (dead plant) phytotoxicity rating by Bartley et al. (2016).

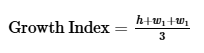

Three studies also included a composite index. In all cases, this index included crown (canopy) width and tree height. Richardson et al. (2008) and Bartley et al. (2016) used the same index but formulated differently. The index can be given as

where h is tree height and w1 and w2 are the perpendicular crown width measurements. Greenly and Rakow (1995) used a different composite index, the formula for which is given as

where h is tree height, w is a singular crown width measurement, and c is the tree caliper.

Summary of Findings

Results across the studies varied; study findings were conflicted on whether increased mulch depth is detrimental to tree physiology. In addition, many of the variables in Table 2 were only examined by one study or, if examined by multiple studies, were examined under different biophysical conditions or using different methods. There are also data handing issues (e.g., data lost for phosphorous [Stafne et al. 2009] and reporting limitations or gaps that preclude further analysis). For example, Billeaud and Zajicek (1989a) examined 4 different mulch types but examined the effect of mulch depth on new growth without a mulch type factor. With these limitations in mind, we summarize the 11 studies’ findings in the following subsections.

Impact of Mulch on Tree Physiology

Tree Mortality: Arnold et al. (2005) found that mulch depth had a significant effect on tree mortality, increasing with increasing depth. Mulch depths as little as 7.6 cm (3 inches) led to increased tree mortality, and mortality rates were more profound for Koelreuteria bipinnata. Stafne et al. (2009) found that tree mortality increased with mulch depth, increasing from less than 5% mortality in 5 cm (2 inches) or less of mulch to 15% in 10 cm (4 inches) of mulch and 35% in 15 cm (6 inches) of mulch. They attributed this to atypically high precipitation rates with greater soil moisture under the 10- and 15-cm (4- and 6-inch) mulch depths. In contrast, Hild and Morgan (1993) found that tree mortality did not differ with mulch depth after 18 months.

Tree and Foliage Condition: Arnold et al. (2005) found that mulch thickness had a significant effect on the percentage of the canopy with symptoms of foliar stress (including “chlorosis, marginal necrosis, and/or premature leaf senescence”), generally increasing with mulch depth. Billeaud and Zajicek (1989a) found that differences in visual appearance were not statistically significant between mulch and non-mulch treatments, except for pine mulch, which had a significantly lower rating than the four other mulch types and the control. The effect of mulch depth was not reported. Bartley et al. (2016) measured phytotoxicity ratings, finding no phytotoxicity, although the statistical results are not reported for mulch depth. Hild and Morgan (1993) found that canopy fill did not significantly differ between mulch depths.

Trunk Diameter: No study reported an effect of mulch depth on changes in trunk diameter. Arnold et al. (2005) and Hild and Morgan (1993) found that mulch thickness had no significant effect on trunk diameter. Gilman and Grabosky (2004) found that there was no difference in caliper growth between 0-cm (0-inch), 7.5-cm (3-inch), and 15-cm (6-inch) mulch depths when mulch was applied over the root ball. Greenly and Rakow (1995) found that caliper was greater for mulched versus unmulched trees, but the effect of mulch depth on caliper was not reported.

Trunk Area: Foshee et al. (1996) and Stafne et al. (2009) both examined trunk cross-sectional area (TCSA). Foshee et al. (1996) found that TCSA increased with increasing mulch depth, although there was little difference between 20 and 30 cm (8 and 12 inches) of mulch depth. Stafne et al. (2009) found that TCSA was higher with mulch than without, but TCSA between mulch depths did not significantly differ.

Shoot Growth: Greenly and Rakow (1995) found that shoot growth was significantly greater at 7.5-cm mulch depth than, in order of greatest to least shoot growth, 15, 0, and 25.5 cm (6, 0, and 10 inches) of mulch. The differences for oak shoots were more profound than pine shoots, and oak shoots had notably lower growth than 0 cm (0 inches) of mulch depth. Pellett and Heleba (1995) found that 10-cm (4-inch) mulch depth had reduced growth rate versus 5-cm (2-inch) mulch depth. Billeaud and Zajicek (1989a) found that shoot dry weights did not differ between mulch types and bare soils except for pine mulch, which had the lowest shoot dry weights, but did not report the effect of mulch depth. However, Billeaud and Zajicek (1989a) found that increasing mulch depth from 0 to 15 cm (0 to 6 inches) resulted in decreasing new growth.

Crown Width: Hild and Morgan (1993) measured crown width as the average of the greatest horizontal crown width and its perpendicular crown width. They found no significant difference in crown width across 0, 7.5, and 15 cm (0, 3, and 6 inches) mulch depths.

Tree Height: Arnold et al. (2005) found that mulch thickness had a significant effect on the height of Fraxinus pennsylvanica but did not have a significant effect on the height of Koelreuteria bipinnata. The study did not include a post-hoc test for pair-wise comparisons, but the authors reported that mulching had a negative effect on F. pennsylvanica height at mulch depths greater than 7.6 cm (3 inches) when trees were planted at or above grade. The lack of height reduction for below-grade planting under 7.6 cm (3 inches) of mulch depth was attributed to the low survival rate of the trees planted below grade (Arnold et al. 2005). Hild and Morgan (1993) found no significant difference in tree height across 0, 7.5, and 15 cm (0, 3, and 6 inches) of mulch depths. Stafne et al. (2009) found that tree heights were greater for mulched than bare soil but found no significant difference in tree height across 5, 10, and 15 cm (2, 4, and 6 inches) of mulch depth.

Roots: Sun et al. (2023) found that 5 cm (2 inches) of mulch produced the most positive effects on fine root morphology at 6 months of mulching but was surpassed by 10 and 20 cm (4 and 8 inches) of mulch in the 9th and 12th months of mulching. Sun et al. (2023) also found that specific root length, specific surface area, and fine root biomass were lower in 5 cm of mulch while root tissue density was higher in 5 cm (2 inches) of mulch than the 10 and 20 cm depths (4 and 8 inches). Billeaud and Zajicek (1989a) found that root dry weights did not differ between mulch types and bare soils but did not report the effect of mulch depth.

Composite Indices: Bartley et al. (2016) and Richardson et al. (2008) found no impact of mulch depth on tree growth measured via their shared composite index. Greenly and Rakow (1995) found that mulch depth had a significant influence on growth, measured via their index (width × height × caliper), but the directionality of the association was not reported.

Impact of Mulch on Soil Chemistry and Temperature

Soil Moisture and Water Content: Broadly, soil moisture and water content were found to be higher under a layer of mulch, although the optimal layer of mulch was unclear. No mulch leads to water loss from evaporation, but deep mulch depths may inhibit irrigation or precipitation (Arnold et al. 2005) or retain too much water (Stafne et al. 2009). Arnold et al. (2005) found that soil water potential was least negative under 7.6 cm (3 inches) of mulch compared to bare soil or mulch depths up to 22.9 cm (9 inches). Similarly, Sun et al. (2023) found that mean soil water content at 0 to 20 cm and 20 to 40 cm was generally higher under 10 cm (4 inches) of mulch than 0, 5, and 20 cm (0, 2, and 8 inches). In contrast, Greenly and Rakow (1995) found that soil moisture increased with increasing mulch depth from 9.8% mean soil moisture with no mulch to 17.4% mean soil moisture with 25 cm (10 inches) of mulch, although differences between mulch depths were not significant. These findings may be due to the testing approach: Greenly and Rakow (1995) tested soil moisture one week after precipitation whereas Arnold et al. (2005) monitored soil water potential throughout the first growing season and Sun et al. (2023) measured at 6, 9, and 12 months after mulch application.

Soil pH: The impact of mulch depth on soil pH was equally unclear. Sun et al. (2023) found that soil pH generally increased with increasing mulch depth while Billeaud and Zajicek (1989a) found that soil pH was decreased with increasing mulch depths. Stafne et al. (2009) found that soil pH decreased with mulch than without, although there were no consistent trends with increasing mulch depth. Greenly and Rakow (1995) found pH to be unaffected by mulch depth. Similarly, Hild and Morgan (1993) found that soil pH was typically unaffected by mulch depth (n = 15), although in the few cases where it did (n = 3), soil pH decreased with increasing mulch depth.

Soil Salinity: Two studies tested soil salinity. Hild and Morgan (1993) found that soil electrical conductivity was significantly lower under mulch versus no mulch, but there were seldom differences between the 2 mulch depths of 7.5 and 15 cm (3 and 6 inches). Greenly and Rakow (1995) tested soluble salt concentration but did not examine it in the context of mulch depth.

Soil Nutrient Levels: Four studies examined soil nutrient levels, producing conflicting results. Greenly and Rakow (1995) found no relationship between mulch depth and nitrates. Billeaud and Zajicek (1989a) found that soil nitrogen was significantly lower under mulch than bare soils but found no significant differences between mulch depths of 5, 10, and 15 cm (2, 4, and 3 inches). Sun et al. (2023) did not report all soil nutrients analyzed, but 10 cm (4 inches) of mulch generally had higher soil organic carbon, ammonium, nitrate, microbial biomass carbon, and microbial biomass nitrogen while 20 cm (8 inches) of mulch generally had higher total phosphorus. Soil tests by Pellett and Heleba (1995) “showed little difference” for 6 nutrients and “small differences” for 7 heavy metals under mulch versus bare soil, but the effect of mulch depth was not reported.

Soil Oxygen: Greenly and Rakow (1995) were the only study to examine percent oxygen for mulch depths, finding a non-significant decline in percent oxygen with increasing mulch depths. The difference between 0 cm (0 inches) of mulch and 25.5 cm (10 inches) of mulch was only 0.9% soil oxygen.

Soil Temperature: The effect of mulch depth on soil temperature was examined in 3 studies. Greenly and Rakow (1995) found that the mean soil temperature in summer decreased with increasing mulch depth, although the difference became less pronounced into late September. There was often no significant pair-wise difference between 0 and 7.5 cm (0 and 3 inches) of mulch nor 15 and 25 cm (6 and 10 inches) of mulch. Pellett and Heleba (1995) found that soil temperature decreased with increasing mulch depth during afternoon temperatures but had little difference around sunrise. The difference between 5 cm (2 in) and 10 cm (4 inches) of mulch was less than the difference between 0 cm (0 inches) and 5 cm (2 inches). Sun et al. (2023) recorded no consistent trend in soil temperature under various mulch depths.

Impact of Mulch on Pathogens and Weed Control

Pathogens: After piling up mulch around the trunk, Greenly and Rakow (1995) found no visible discoloration or colonization by pathogens or cankers. Greenly and Rakow (1995) also cut wounds into the trees prior to planting, which had grown normal preventative calluses.

Weed Control: There were 5 studies that found that deep mulch applications provided the greatest weed control (Billeaud and Zajicek 1989a; Greenly and Rakow 1995; Pellett and Heleba 1995; Richardson et al. 2008; Stafne et al. 2009) with maximum mulch depths ranging from 7.5 cm (3.0 inches)(Richardson et al. 2008) to 25 cm (10 inches)(Greenly and Rakow 1995). However, at least some weed control benefits were provided with as little as 5 cm (2 inches) and 7.5 cm (3 inches) of mulch (Billeaud and Zajicek 1989a; Greenly and Rakow 1995).

Influence of Environmental Factors on Results

Several studies noted the potential impact of adverse weather. Arnold et al. (2005) noted that dieback on Koelreuteria bipinnata may have resulted from tip dieback in a late winter freeze. Gilman and Grabosky (2004) noted in their methods that a period of very hot and dry weather required supplemental irrigation. Some trees dropped a portion of their foliage, one lost all its leaves, and one died. Greenly and Rakow (1995) had the opposite issue: an above average year of precipitation during their no-irrigation study year likely reduced the effect of the mulch layer on water conservation. Similarly, Stafne et al. (2009) reported increasing tree mortality with increasing mulch depth but attribute the primary reasons to record rainfalls in the second study year. These influences reflect the general struggles of arboricultural and botanical research outside a controlled greenhouse experiment. This is reflected by Hild and Morgan (1993) who warn that results would differ under moisture limited environments, faster mulch decomposition, and in the absence of weed control.

Discussion

Popular ideas without scientific observation can become commonly held perceptions, a pervasive occurrence in the landscaping industry (Gillman 2008; Chalker-Scott and Downer 2020). These perceptions occasionally become so well-regarded that they appear in extension publications that are used by practitioners for educational purposes, despite lacking the support of scientific observations (Chalker-Scott and Downer 2018). Our mini review of the peer-reviewed literature on the impacts of deep mulch on tree physiology finds that while data show mortality and some growth parameters can be negatively impacted by excessive mulch depth, there is inconclusive evidence to establish a definitive threshold beyond which tree health is compromised. Whether deep mulching impacts trees, and the depth at which impacts occur, is likely dependent on soil and mulch type, soil water quantity, and species niches, including tolerance to water logging and organic matter deposition. Study designs, statistical approaches, and extraneous and nuisance variables preclude comparisons between studies. However, while studies differed in whether trees grew better with mulch depths beyond 10 cm (4 inches), no study found that tree survival was negatively impacted by planting within 5 to 10 cm (2 to 4 inches) of mulch.

A notable difference between studies is the type of mulches used. Not all mulches perform the same, and there are great differences in the effects of mulch type on plant growth and soil characteristics (Litzow and Pellett 1983). Not included in our review is a study by Watson and Kupkowski (1991) that compared 45 cm (18 inches) of coarse mulch to areas without mulch. While this study was not included in the review because it did not compare multiple mulch depths, Watson and Kupkowski (1991) found that the 45-cm-deep (18-inch-deep) mulch did not impact trees. Based on their findings, it is possible that the negative impacts of deep mulching are a consequence of finer mulch that becomes akin to soil. This is supported by Billeaud and Zajicek (1989a) who found that pine bark mulch, which was the smallest, densest mulch examined, resulted in the poorest visual plant rating, growth, and shoot dry weight. This aligns with a tree planting book by Watson and Himelick (2013), who wrote that fine textured mulch could reduce soil oxygen under wet conditions, even when applied with as little as 5 cm (2 inches).

Fine textured mulch would essentially raise the soil profile, causing the stem encircling or girdling roots noted in studies where trees were planted too deeply (Wells et al. 2006; Day and Harris 2008; Harris et al. 2016; Hauer and Johnson 2021). These girdling roots negatively affect trunk taper (Day and Harris 2008). Wells et al. (2006) also found reduced survival rates in deeply planted trees. This would explain the observations by practitioners and extension specialists who may be inferring that girdling occurs as a consequence of the soil profile being raised.

Additionally, the application of mulch increases soil moisture in both the mulch and underlying soil when compared to unmulched, grass areas (Watson 1988). This can improve survivability under drought conditions, but can cause mortality under extended flood conditions, as was observed by Stafne et al. (2009). As a result, studies on mulch depth undertaken during drought conditions will likely reach different conclusions than studies on mulch depth undertaken during flood conditions. Similarly, Drilias et al. (1982) proposed that deep planting (root collar 15 to 25 cm [6 to 10 inches] below grade) may lead to increased canker occurrence. If the decay of fine mulch leads to the more soil-like properties, this may explain the correlation between excess mulch depth and an increased incidence of pathogens reported by practitioners and extension specialists. Further study is needed on pathogen prevalence in both deeply planted trees and deeply mulched trees.

Additional Literature

Outside of the peer-reviewed literature, other formal studies have been conducted but remain unpublished. In 2010, the Tree Research & Education Endowment (TREE) Fund (Naperville, IL, USA) funded a research project titled “Evaluating damage resulting from volcano mulching”. Based on the project’s examination of 84 trees in Chicago, what appeared to be mulch volcanoes were actually thin mulch layers covering soil mounds, resulting from improper planting or maintenance practices (Watson 2014b). Both the soil mounds and mulch were well-aerated, and 80% of surveyed trees showed no disease symptoms. However, one-third of the trees had problematic encircling or stem girdling roots. Additional research on container-grown trees revealed that trees with volcano mulch exhibited more wound-related discoloration, suggesting this mulching practice may increase vulnerability to damage. However, the study found that while disease-causing fungi were isolated from volcano mulched trees, there was no indication that the fungi were aggressive pathogens, regardless of volcano mulching. Watson (2014b) concludes that “while volcano mulching is not considered best practice, when data from this study is fully analyzed, it is not expected to support the assertion that volcano mulching results in widespread and health-threatening disease development in landscape trees.”

A similar study is described in the MS thesis of Giblin (2013), which investigated the impact of wounding and mulch depth on the growth and internal discoloration of 48 Northwoods red maple (Acer rubrum ‘Northwoods’). Shredded wood mulch was applied with and without contact with the stem through 3 variations: 15 cm (6 inches) of mulch with no contact to the stem, 15 cm (6 inches) of mulch with contact to the stem, and 30 cm (12 inches) of mulch with contact to the stem (Giblin 2013). After 30 months, destructive harvesting found that the trees with 30 cm (12 inches) of mulch against the stem had significantly greater number of twig nodes and greater final stem area than the two 15-cm (6-inch) mulch treatments. Across the mulch treatments, there was no significant difference in wound occlusion nor stem discoloration cross-sectionally or vertically, in contrast to the findings reported by Watson (2014b).

Limitations of Our Review

Because we excluded non-English studies, this review may exclude additional studies on the impacts of deep mulch applications on trees. However, because the included studies are conflicting, we are accurately presenting the existing dichotomy. One or two additional non-English studies would further emphasize this existing dichotomy, rather than providing support for a clear maximum mulch depth. Similarly, we conducted our search in 5 databases and 11 journals, following the search protocols of Martin and Conway (2025), which includes searching the commonly read journals of arborists and urban foresters (Martin et al. 2024). This approach therefore identifies relevant studies in non-indexed journals like Arboriculture & Urban Forestry (Hauer and Koeser 2018). This can introduce bias into the results as it may exclude studies in non-indexed journals outside of the 11 journals that we searched. However, backward citation searching helped address this bias by identifying literature cited by studies that we found through our search.

While our review examined peer-reviewed literature, we have identified two unpublished studies in the Discussion (Giblin 2013; Watson 2014b). We have also excluded articles published in informally reviewed trade magazines like Arborist News. Many such articles, including those in the Introduction, attempt to synthesize practitioner observations or scientific literature (although often without citations). These articles are not review papers nor research studies themselves. While both unpublished or informally reviewed studies can contribute to the development of best practices, they have not undergone the rigour of the peer review process and are often remiss of the required methodological elements of a publishable scientific study (Gastel and Day 2016).

Future Research and Recommended Study Design

While studies have identified the minimum mulching depth required to improve soil health, plant growth, and weed control (Chalker-Scott 2007), there is no clear maximum depth from peer-reviewed literature. Further research should seek to identify maxima based on mulch type. We recommend that future studies consider 5 items in their research design and reporting.

First, researchers must report the type of mulch used (e.g., pine bark mulch), the time that it has been dried (e.g., 3 months of drying before application), and its physical and chemical properties when applied and at the time of excavation. Sun et al. (2023) provide a good table of the properties of their mulch.

Second, researchers should consider the biophysical factors beyond the tree and mulch. The soil properties, weather and climate data, and use of supplemental irrigation should be included in the study. Physical and chemical properties of the soil influence tree health, root defects, and moisture retention. The study area’s climatic norms and weather data for the duration of the study are also important for interpreting the results for other climatic zones.

Third, researchers must include both a control group (no mulch) and several depths of mulch (e.g., 10, 20, and 30 cm [4, 8 and 12 inches] of mulch). The depths should include depths both within and above the recommended mulch depths from best management practices and standards, often 5 to 10 cm (2 to 4 inches).

Fourth, researchers should consider the width and slope of the mulch ring and its proximity to the trunk. These are additional factors that may be cofounding variables. A deep, widely mulched ring may cause more girdling. Mulch that is piled with a high slope may cause rainwater to run away from the trunk instead of infiltrate through the mulch pile, although there are no research studies that introduce these concepts. The proximity of mulch to the trunk may impact occlusion and growth (Giblin 2013).

Fifth, researchers should note the planting depth of the trees. The previous findings cited in our Discussion that highlight the impact of planting depth (e.g., Wells et al. 2006; Day and Harris 2008; Hauer and Johnson 2021) indicate that this could be a confounding factor in root encircling or constricting the trunk.

In addition to these 5 research design and reporting recommendations, it is also important that researchers published non-significant results. The finding that there is no difference between conventional and deep mulching is, in and of itself, a substantial result and one that will be beneficial for practitioners.

Conclusion

While there are many benefits to applying mulch around the base of urban trees, practitioners and extension specialists often warn about the deleterious impacts of excessive mulch depth. It is commonly believed that mulch exceeding 10 cm (4 inches) can lead to girdling or encircling roots and poor tree growth. Our literature review identified 11 studies that tested the impact of mulch depth on tree physiology, as well as soil physiology, water conservation, pathogens, and weeds. Due to differences in study methods and tested variables, the impact of deep mulch remains inconclusive though there is evidence that mulch depth over 10 cm (4 inches) can have negative impacts on growth in some instances. Differences in biophysical and climatic factors, tree species, and mulch type and porosity explain many of the observed differences in outcomes, resulting in some researchers finding greater mulch depth beneficial while others report negative impacts. At present, there is no clear maximum mulch depth that leads to declining tree condition. We emphasize the need for future research that focuses on mulch depth and tests physiological variables of trees. Future research should follow the 5 research and design recommendations for ensuring quality studies as presented in this review. By expanding the literature on mulch depth, extension papers, educational materials, and industry BMPs and standards can better reflect scientific findings.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Anna Heckman for her help in searching for archival resources. Thank you to Lindsey Mitchell of the International Society of Arboriculture (ISA) for providing scanned copies of Arborist News from the ISA archives.