Students as Researchers: An Inquiry into University Courtyards as Diverse and Inclusive Areas for Social Connection and Wellbeing

Background

Urban forests enhance mental health by reducing loneliness, fostering connections to nature, and reducing stress and anxiety. There is growing interest in understanding how urban forests can help support mental health across the life course, including among young adults. Given the known psychological and social benefits of nature-rich environments, it is critical to evaluate the functionality and usage of urban forest spaces for specific groups, particularly those at higher risk of mental health conditions like the members of this age group.

Methods

This student-led research study at the University of British Columbia’s Vancouver campus applied a mixed methods approach to assess the role of campus courtyards in supporting student wellbeing, with the ultimate aim of informing inclusive and effective spatial planning. Eight courtyards were analyzed via surveys and participant observation to understand their restorative and social benefits. Involving students as researchers played a vital role in offering alternative perspectives that helped identify previously overlooked gaps in this field.

Results

Our findings highlight the value of nearby, convenient greenspaces for young adults. There were 46 survey participants who shared their experiences in UBC courtyards, focusing on restorative and social benefits; 139 courtyard uses were observed by student researchers. Courtyards varied in biodiversity, order, and seclusion. Biodiverse courtyards received higher ratings for restoration, while social courtyards were linked to less reported guilt due to taking breaks. Across courtyard design typologies, students valued privacy, vegetation, and a sense of inclusion, although feelings of loneliness and discontent persisted.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the value in engaging students as researchers to understand student perceptions of a campus urban forest for supporting wellbeing, social connection, and academic achievement. Although greenspaces such as courtyards are known to have restorative potential, they are not always designed to fully support student needs, highlighting the importance of student-informed planning frameworks that address existing gaps and foster more accessible, functional, and representative greenspaces on campuses.

Introduction

As our understanding of the health benefits of exposure to urban forests has developed (Cox et al. 2017; Nieuwenhuijsen et al. 2022), it has become clear that a diversity of experiences and user perspectives must be taken into account to maximize these benefits (Bratman et al. 2021; Larson et al. 2022). In response, recent studies have sought to understand variations in people’s experiences of urban forests as they age, as well as the ways in which those experiences have a differential impact on wellbeing at specific points in human growth and development (Besser et al. 2023). A recent systematic review found that biodiversity and natural characteristics of greenspaces—a broad category that includes urban forests as well as more tended areas that feature vegetation, such as parks, green roofs and walls, laneways and transit corridors, and plazas and courtyards—support human wellbeing by enhancing health, particularly mental health, and by fostering positive social interactions (Reyes-Riveros et al. 2021).

One population that has been less studied in urban forest research is young adults, those aged 18 to 25 (Peterson et al. 2024), despite the fact that members of this group are particularly vulnerable to poor mental health. Three-quarters of lifelong mental health conditions emerge at this age (Kessler et al. 2003); self-harm is a leading cause of death among young adults aged 15 to 24 (Ward et al. 2021); and COVID-19 sharply increased levels of psychological distress within this group (Wiedemann et al. 2022). In addition to these psychological vulnerabilities, young adulthood is a critical period for establishing lifelong behaviour patterns, including a relationship with nature, but studies have shown a decreasing amount of time spent in nature (Zamora et al. 2021) and an increasing sense of disconnection (Whitten 2025) at this age in comparison to earlier in life. Finally, urban forests may provide a particularly important location for fostering social connections among young adults (Collins et al. 2024), especially those individuals residing in dense urban environments, which have been linked to higher levels of isolation and loneliness (Moore 2003).

Seeking to fill this gap, the role of university campus environments in supporting student wellbeing has grown in interest (Li et al. 2024). Emerging research emphasizes the importance of designing spaces that cater to the specific needs and preferences of diverse student populations (Ha and Kim 2021; Sun et al. 2021; Guo et al. 2023). Alves et al. (2022) point to the role of biophilic attributes in enhancing students’ sense of connection, suggesting that spaces designed specifically for social interaction can improve students’ perceptions of both the space and nature as a whole. Conversely, enclosed classrooms and densified urban campuses that lack natural elements can amplify stress and anxiety (Peters and D’Penna 2020; Alves et al. 2022), potentially increasing feelings of isolation and loneliness in the student population.

Sun et al. (2021) emphasize the varying restorative impacts of different types of campus environments, highlighting the importance of incorporating diverse landscape types, including both greenspace and bluespace (such as streams, ponds, and even fountains), to cater to a wide range of preferences and needs. Here, we use ‘urban forests’ as an umbrella term to capture the diversity of nature found across university campuses. Moving beyond the broader design elements captured above, emerging evidence indicates that this specific aspect of campus design can be critically important for student success, health, and social connections. Studies have shown that urban forests on campus play an important role in student learning and engagement, increasing attention (Lee et al. 2015; Alves et al. 2022), improving mental wellbeing (Ha and Kim 2021; Guo et al. 2023; Wen et al. 2025), and supporting a sense of belonging (Menatti et al. 2019). These greenspaces can also increase a sense of connectedness to nature, or CTN (Alves et al. 2022), offsetting the so-called “teenage dip” (Hughes et al. 2019).

Urban forests grow across our campus communities in a myriad of conditions and range of sizes, making it vital to identify the restorative effects of specific characteristics, including size, plant configurations, relationship to buildings, and location of outdoor furniture (Li et al. 2024). Additionally, many studies have overlooked the diverse cultural, social, and personal factors that influence how individual students interact with campus spaces, limiting the design of inclusive environments that support the mental health of all students, particularly members of underrepresented groups such as international students or those with disabilities.

Our current research effort seeks to fill these gaps in the literature while also responding to calls to integrate young adults’ voices into greenspace research and design processes (Alnusairat et al. 2022; Barron and Rugel 2023) via the participation of young adult researchers. Student researchers contributed as equals in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and writing of this project. In addition, student researchers selected the unique setting for this study—campus courtyards—highlighting their potential as informal meeting places connected by a network of pathways and trails that provide green routes. Taking their lead, our mixed methods approach combines biodiversity audits, participant observation, and a brief survey of courtyard visitors to uncover nuances in how students experience campus courtyards as a specific form of urban forests.

Methods

Location

This study took place on the University of British Columbia (UBC) campus in Vancouver, Canada, which is set 10 km from downtown Vancouver and occupies 402 ha on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territories of the Musqueam people. In 2024, UBC Vancouver had 48,149 undergraduate and 11,139 graduate students. The university operates on a semester system, with 2 longer terms in the winter (roughly 4 months each) and 2 short terms in the summer (approximately 1 month duration). Most students take courses during both the fall (September to December) and spring semesters (January to April). Our study took place in the fall semester of 2024.

This study adopted a ‘researchers as participants’ approach where 5 undergraduate student researchers, all young adults, led key aspects of the research with structured mentorship from a faculty member. The student researchers coproduced the survey with the assistance of the faculty member and worked independently in conducting biodiversity audits and participant observations. With support from the faculty member, the students analysed the data and assisted in the drafting and editing of the manuscript. The faculty member provided guidance throughout the study, including methodological training during the study design phase; facilitating research group discussions during site selection and data analysis; and offering feedback and collaboration on survey development and manuscript drafting. Mentorship occurred during weekly group discussions and ad-hoc consultations as needed, ensuring students had significant autonomy while benefiting from expert oversight. This balance allowed students to drive the research process while leveraging faculty expertise to refine their work.

To investigate student uses and preferences for campus spaces, the research team selected a range of campus courtyards that students might use throughout the day. Campus courtyards (see Figure 1) were selected as the study’s setting by student researchers because they are located near classrooms, provide seating, and are designed for restorative and/or social activities. The research team mapped all potential campus courtyards, identifying 22 potential sites. Two student researchers spent time at each of the identified courtyards to assess their potential for restoration, focusing on three qualitative criteria: perceived biodiversity (e.g., presence of diverse plant species); capacity for seclusion (e.g., presence of enclosed or quiet areas); and degree of order and maintenance (e.g., cleanliness, upkeep of landscaping). These assessments were based on visual observations and the researchers’ experiences as students, without formal scales, to prioritize the selection of sites aligning with young adults’ likely preferences.

Figure 1.

Locations of campus courtyards measured in this study (pink boxes).

Following these initial visits, the research team convened a group discussion to narrow the initial list of 22 to 8 specific sites for detailed study. This discussion involved ranking sites based on the 3 criteria (biodiversity, seclusion, and order) to capture a range of courtyard types. Additional considerations included proximity to academic hubs (e.g., classroom buildings, cafes) and high student traffic, as the student researchers believed these factors would increase student use, advancing the study’s feasibility. Other variables—including accessibility (e.g., wheelchair access) and comfort features (e.g., shade, benches), ecological, and spatial characteristics—were also taken into consideration. The 8 selected courtyards were spread across campus while being located near major academic hubs and main campus walkways, ensuring relevance to the young adult population.

After site selection, biodiversity audits and observational measurements (see below) provided quantitative data on biodiversity, seclusion, and order, which informed the grouping of the 8 courtyards into 4 pairs. This grouping was achieved through team consensus, aligning with Barron and Rugel’s (2023) framework for tolerant greenspaces, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Qualities of campus courtyards. We grouped the 8 courtyards into pairs according to their qualities of biodiversity, order, and seclusion (adapted from Barron and Rugel 2023). Two courtyards scored highly in all three qualities. Four courtyards scored medium for two categories and low in one. Two courtyards scored low in diversity and order, but medium for seclusion.

Biodiversity Audits and Observational Measurements

On an initial visit in September or October, a team of two student researchers completed a robust biodiversity audit at each site. Parameters measured included plant species, size, and a range of functional plant traits such as leaf shape, size, bark texture, and presence of fruits or flowers. Because data were collected in the fall, not all traits were observable.

As a complement to these audits, observational measurements were drawn from the Survey Instrument for Plaza Stationary Activity Scans (Kim 2016), prioritizing variables that the student researchers felt resonated with their personal campus experiences. The key adaptation was to add ‘studying’ as a potential activity, as suggested by the student researchers. Observations were taken at each courtyard in October and November during 3 separate visits by a single student researcher that lasted between 1 and 3 hours apiece in a range of weather conditions. This timing was guided by the student researchers’ interest in capturing data during potentially stressful times for the young adult population of interest, including exam periods.

Grouping the courtyards into pairs occurred after the observational and biodiversity measurements, which allowed the students to better understand the qualities of each space. Following a discussion, the research team came to a consensus that the courtyards naturally grouped into 4 pairs (Figure 2). The first pair, biodiverse courtyards, had similar characteristics of a high biodiversity of plants, high amount of planted material, and less open space for social activities. The next pair, open courtyards, had less plant material and more unprogrammed space, giving an impression of extent with less seclusion. The third pair, social courtyards, had cohesive designs focused on social spaces, with lower biodiversity and less sense of seclusion. Finally, the last pair, forgotten courtyards, ranked low across all 3 qualities except seclusion, because they were tucked away and had fewer signs of maintenance.

Survey

Signs were posted in each courtyard encouraging visitors to participate in a short online survey, along with a QR code link to the survey itself. Student researchers also approached users of the space with the survey link. Because the UBC campus hosts a number of facilities that are used by members of the public—including a hospital, museums, and sports and event facilities—participation was open to undergraduate and graduate students, faculty and staff members, and visitors to campus in order to increase the total number of participants. As a mixed methods study, we did not pre-specify an adequate sample size figure but instead sought to collect enough data to reach saturation during thematic analyses.

The survey was developed iteratively by the entire research team with students offering feedback on how they would interact with such a survey and what the optimal length would be to encourage participation by their peers. Each member of the team identified potential items from other campus environment studies, testing them with the team as a whole, and adapting them for the young adult population. Adjustments were made to individual items to ensure clarity and to make them comprehensible from the perspective of both researchers and students. Importantly, two of the student researchers edited items to ensure they were understandable by individuals with dyslexia and ADHD. We strove to create surveys that felt approachable and empathetic, rather than harsh, intrusive, or dehumanizing.

The survey included basic demographic questions, including gender identity and relationship to UBC. Participants were asked questions to gauge their current psychological state, including their ability to concentrate and their feelings of loneliness. They were then asked questions about their experience of the courtyard space they were using. The psychological questions included a short version of Hartig et al.’s (1991) Perceived Restorativeness Scale (PRS)(Negrín et al. 2017), which gauges whether a space induces feelings of ‘being away’, ‘fascination’, ‘coherence’, ‘compatibility’, and ‘scope’. Our survey also included questions to learn more about how using the space made participants feel, how often they used the space, and why they used the space. All items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’. The Appendix includes the full survey instrument.

To gauge feelings of social connectedness, we chose the 3-item UCLA Loneliness Scale because it was brief but effective (Hughes et al. 2004) and because the language resonated with the student researchers. We used the same Likert scale as the loneliness questions because the student researchers agreed that a consistent scale across measures was easier for participants to follow. As a result, this survey component was scored slightly differently than typical applications, which ask participants to respond ‘hardly ever, some of the time, often’ to each item and for which a score of 3 to 5 is categorized as ‘not lonely’ while 6 to 9 is ‘lonely’ (Hughes et al. 2004). Finally, two open-ended items asked participants to complete a sentence, offering additional insights into their other survey responses. The prompts were: “I spend time here because…” and “After spending time here, I feel…”.

Human Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the UBC Research Ethics Board prior to collecting participant data, and all analyses were conducted in Microsoft Excel for Mac, version 16.91 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA).

Results

Participants

A total of 46 full survey responses were recorded. Of the participants, 25 identified as female, 19 as male, and 2 as nonbinary. Undergraduate students made up 37 participants, 4 were graduate students, 4 were faculty/staff members, and 1 was not affiliated with UBC.

Research suggests that many university students experience chronic stress and that this stress can impact their ability to succeed in the classroom environment (Foellmer et al. 2021; Guo et al. 2023; Wen et al. 2025). In order to get a sense of how participants were currently performing, we collected data on participants’ abilities to concentrate and to pay attention. Participants were generally neutral on their reported ability to pay attention and/or concentrate on long lectures. In response to the question “Typically, I can concentrate on full lectures” using a 5-point Likert scale, the average response was 3.45, between neutral and somewhat agree. Broken down, 22 participants ‘somewhat agreed’ that they could concentrate on a full lecture, while 17 ‘somewhat disagreed’, and 7 were neutral. When asked about their ability to “pay attention to a long lecture (over one hour)”, the average response was 3.17.

When asked about loneliness, on average, participants indicated that they were lonely. Responses ranged from 3 to 9 out of a total of 9 on our adapted version of the 3-item UCLA Loneliness Scale, with an average of 6.17. A score below 6 indicates that participants did not feel they lacked companionship, felt left out, or felt isolated; a score of 6 or greater indicates that participants sometimes felt these 3 dimensions of loneliness; a score of 9 indicates that participants often felt this way. In detail, 12 participants (26%) scored under 6, which we categorized as ‘not lonely’, while the remaining 34 (74%) participants were categorized as ‘lonely’.

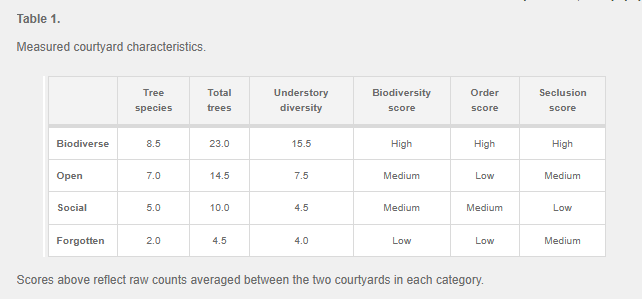

Biodiversity and Other Courtyard Characteristic

To elucidate the survey findings, we measured the characteristics of each courtyard, including biodiversity, exploring connections between courtyard characteristics and participant responses. Select results on the measured biodiversity, order, and seclusion of the 8 courtyards are shown in Table 1. We report biodiversity in terms of number of species. Some courtyards had only one type of tree, while others had up to ten unique species. Understory diversity ranged from one to seven species. Order was categorized by researchers as ranging from ‘low’ to ‘high’.

The survey asked participants to list any features that attracted them to a space, with nearly half (20 of 46) mentioning vegetation and trees. Some participants linked these natural features to providing a sense of being away: “It doesn’t look like a school” and it “feels kind of wild and overgrown, the trees and brick building have a fun vibe”. Four participants mentioned specific tree species they connected with: Pinus coulteri, Acer palmatum (two), and Fagus sylvatica. Others noted that large trees provided privacy. One spoke of viewing the courtyard from class: “The bushes and scenery around the buildings give a sense of nature while attending classes”.

Open space was highlighted as important by 5 participants. An opportunity to sit in the sun was mentioned by 3 participants, which is likely important in the rainy autumn months during which this study took place. Shelter from rain was also noted as an attractive feature by 2 participants. Seating, including benches and picnic tables, and amenities such as electrical outlets were noted by 7 participants. Two spoke of the importance of student life and interacting with others: “best times were chilling here before class started in the morning”. In addition, multiple participants mentioned seclusion as attractive: “I like how it’s seemingly private but it has an outlet into the more open portions of Main Mall, it’s a good mixture” and that the courtyard provides “privacy away from walkways”. Other notable features mentioned included proximity to class (4), maintenance (3), and design (2). Two participants also mentioned the red brick colour of one courtyard as an attractive feature.

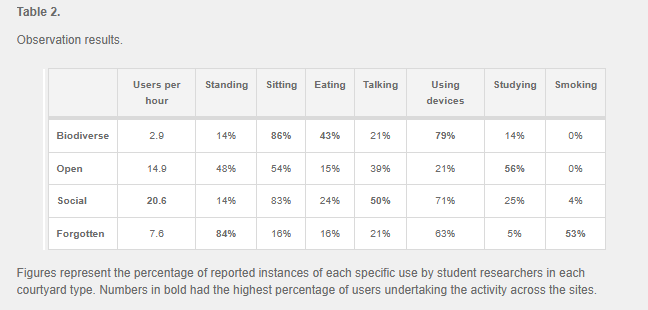

Courtyard Uses

Based on the student researchers’ observations, the number of users at each site varied greatly, ranging from 2.9 to 20.6 per hour, as shown in Table 2. We noticed a divergence in the number of users by courtyard type, with the social courtyards receiving the most visitors per hour, on average. Open courtyards had the second highest number of users, suggesting that university students prefer less-secluded spaces, independent of size. Observational results reveal that higher biodiversity and better maintenance of courtyards were not necessarily valuable characteristics in attracting students. With respect to individual activities, courtyard users were seen eating, talking, watching electronic devices, studying, and smoking. In the social courtyards, talking and studying were primary activities. In biodiverse courtyards, visitors primarily ate and used their phones, while forgotten courtyards were most commonly used for smoking.

Looking next at the survey responses, the most common reasons for visiting courtyards were ‘passing through’ (80%), ‘relaxing and unwinding’ (53%), to ‘enjoy nature’ (46%), to ‘eat or drink’ (37%), ‘getting away’ (35%), and to ‘chat with friends’ (35%).

The potential for courtyards to primarily serve as a transitional space was highlighted by the open-text responses, with 15 respondents completing the phrase “I spend time here because…” with the concept of passing through. These qualitative responses offer additional insights into how simply passing through can still provide a sense of restoration, however, with 8 of the 15 respondents noting that the space was relaxing and others remarking on courtyards as places that provide quiet as well as a safe space for immunocompromised individuals.

Although chatting with friends was a common motivation for visiting a courtyard, most participants reported visiting these spaces on their own (70%). Again, open-ended responses offer a unique perspective on how such solo visits might be restorative, with one participant highlighting the benefits of having a space that “helps me remain centred and enjoy quality time by myself”. Other participants noted that spending time in the courtyard “makes me happy”, “helps me remain centred”, and “releases some stress and anxiety”. One participant noted, “I spend time here because I have to[;] otherwise I’m sad”. Open-text comments also clarified social uses of the courtyards, with 3 participants mentioning using the space to eat lunch or chat with friends.

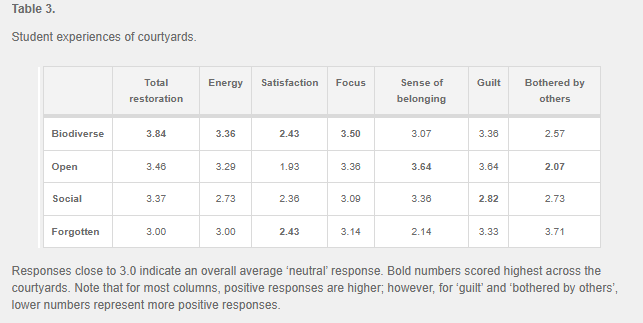

Table 3 shows the results of the survey questions asking whether courtyard visitors feel bothered by the presence of others, or, conversely, whether the presence of others creates a sense of belonging. The overall score was 2.77 for “I feel bothered by the presence of others”, between ‘somewhat disagree’ and ‘neutral’; for “the presence of others creates a sense of belonging”, the overall score was 3.05, just slightly above ‘neutral’. There was little variation in response by courtyard type, although participants felt somewhat less bothered and a greater sense of belonging from the presence of others in the open and social courtyards.

Restorativeness

A key finding was that the biodiverse courtyards that measured highest for biodiversity, order, and seclusion were also those that rated highest for restoration according to the PRS scale, with the exception of the ‘being away’ measure (Figure 3). This finding aligned with the student researchers’ pre-study intuitions that more nature would be more restorative. The forgotten courtyards were more highly rated for ‘being away’, perhaps as a result of their smaller sizes and sense of isolation. In general, the biodiverse courtyards were rated more highly across all PRS measures, while the social courtyards had the lowest ratings.

Figure 3.

Courtyard ‘restorativeness’ according to the PRS scale.

The biodiverse courtyards were also the most highly rated in the survey questions asking about health benefits of spending time in those urban forests (Table 3). The overall findings fell between ‘neutral’ and ‘somewhat agree’ for questions asking about increased energy, balance, and concentration after spending time in these courtyards.

The open courtyards scored lowest for being bothered by the presence of others and highest for feeling that the presence of others creates a sense of belonging. The qualitative responses add some depth to these findings. When participants were asked to complete the sentence “After I spend time here, I feel…”, the majority wrote ‘relaxed’ (10) and/or ‘calm’ (10). Other positive outcomes included: ‘refreshed’ (4), ‘better’ (2), ‘good’ (2), ‘happy’ (2), ‘productive’ (1), and ‘motivated’ (1), with one participant responding that “after I spend time here, I feel like I belong”. Not all participants found a benefit from spending time in courtyards, however: 6 had a neutral response, 2 felt confined, 1 felt stressed that they had to go back to campus, and 1 noted feeling ‘dead inside’.

Discussion

Courtyards Provide Restoration for Stressed University Students

Our study aligns with others that have reported that young adults are facing challenges with psychological well being (Barron and Rugel 2023; Li et al. 2024) and loneliness (Astell-Burt et al. 2022), with a number of qualitative responses offering insights into the ways in which students are struggling with these issues. Our respondents’ lack of ability to ‘concentrate’ and ‘pay attention’ is particularly troubling in light of the fact that 80% were university students who must depend upon these capacities to succeed in their education. Other studies with this age group have demonstrated similar results (Peters and D’Penna 2020; Guo et al. 2023). There is a wide range of potential causes for this inability to pay attention—including poor pedagogy (boring lectures), inconsistent sleep patterns, or overwhelming course loads—and these factors are important to explore in future studies. The higher restoration scores we found for visits to biodiverse courtyards point to a promising trend, corroborated by other studies, that biodiverse nature is especially psychologically restorative (Ha and Kim 2021). Together, these results indicate that increasing biodiversity across campus landscapes could support psychological restoration. Unfortunately, however, the results of our participant observation show that fewer students visit such sites in comparison to open or social courtyards.

We tested the potential for courtyards to serve as psychologically restorative campus spaces via the PRS, finding a connection between high biodiversity and the specific PRS component of ‘fascination’. Visits to biodiverse courtyards were rated as more fascinating, while social courtyards rated low for ‘fascination’. Other components of the PRS have less clear relationships with our biodiversity assessments, although qualitative feedback indicated that participants value courtyards with greater vegetation and few hard surfaces. Openness, captured by the component ‘scope’ in our study, was highest in the biodiverse and open courtyards. Sun et al. (2021) similarly found that ‘extent’ (a sense of space and escape) most clearly connected with restoration in campus spaces. Wen et al. (2025) reported that openness, particularly where building enclosures allowed views of vegetation instead of hardscape, positively impacted evaluations of restorativeness. Height also appears to be important, with Huang et al. (2024) noting that tree height, ground texture, and moderate building heights were all critical to the restoration offered by pedestrian spaces. Through the qualitative comments and restorativeness scores in our study, we note that ‘scope’ was rated highly across courtyard types, suggesting that views of vegetation are an important aspect of restoration in campus urban forests.

Our findings align with previous work highlighting the value of nearby, convenient greenspaces for young adults (Foellmer et al. 2021; Peterson et al. 2024; Whitten 2025) rather than other studies that have asserted that students prefer greenspaces located away from buildings and social campus environments (Windhorst and Williams 2015). The high number of participants reporting that they used courtyards for ‘passing through’ highlights the potential importance of incidental nature exposure, which would benefit from additional research. This possibility is supported by qualitative responses indicating that convenience is a factor in engaging with courtyards. Sun et al. (2021) note that longer exposure to restorative spaces does not necessarily enhance their benefits, indicating that quality and design are more influential than duration.

Diversity of Designs Supports Diverse Opportunities for Wellbeing

Our findings align with Foellmer et al.’s (2021) framework, which suggests that healthy academic spaces exist across a spectrum of experienced, symbolic, and social spaces. The framework suggests that campus greenspaces support student wellbeing in 3 ways: (1) by introducing a restorative effect; (2) by creating campus identity and a sense of belonging; and (3) by creating spaces for social encounters. As shown in Figure 4, different courtyard types can achieve each of these aims, but no single site is sufficient. The variety of spaces and the spectrum of potential wellbeing benefits could explain the neutral responses to our survey questions about health benefits. Our averaged findings fall between ‘neutral’ and ‘somewhat agree’; however, we weren’t able to parse out whether participants were in the right space for their specific needs. For example, a student seeking quiet restoration might not find health benefits from a more socially oriented courtyard design. Cultural and psychological differences may influence responses, and future studies could explore the extent to which specific demographic groups of students are bothered by the presence of others. As noted in other studies (Ha and Kim 2021; Sun et al. 2021), there is no uniform solution to support student wellbeing via the integration of campus nature.

Figure 4.

Healthy academic courtyards (adapted from Foellmer et al. 2021). Our courtyard study did not include active spaces, which would also contribute to physical wellbeing.

hat said, specific design characteristics of vegetation have been linked to greater restoration, including layered hues and textures, softening harsh edges of buildings, and increasing a sense of seclusion from high-stress environments (Huang et al. 2024). Increasing biodiversity does not always provide conditions for restoration, however (Aleves et al. 2022). Some promising trends were highlighted in our observations and survey, particularly related to the social courtyards. Visitors to the open and social courtyards in our study reported higher scores in the socially relevant domains of our survey, with participants suggesting that they ‘somewhat agree’ that the presence of others contributes to their sense of belonging. Interestingly, the social courtyards had a greater number of students who reported low guilt over taking breaks. Perhaps seeing others taking a break alleviates feelings of guilt from taking a break oneself.

Our survey expands upon other studies that have found that young adults are lonely (Astell-Burt et al. 2022) while also highlighting the difference between feeling lonely and spending time alone for restoration (Zhang et al. 2024; Rodriguez et al. 2025). As we observed, and as qualitative responses within our survey reveal, solitary restoration in urban forests is an important activity for young adults. These findings align with those of a study in Australia which reported that young adults found respite in greenspaces for solitary restoration during the COVID-19 pandemic, continuing this behaviour following the lifting of public health restrictions on group activities (Peterson et al. 2024). Increasing opportunities for social engagement appears to be an important contribution of urban forests to student wellbeing, but providing spaces for solitary restoration is similarly important, with our study indicating that biodiversity is a key quality to include in spaces designed to achieve the latter aim.

Biodiversity can take a range of forms. Although the student researchers measured a wide range of biodiversity attributes, we only report tree species diversity and understory diversity. Functional trait diversity, fauna diversity, and fractal patterns are important considerations beyond the scope of our study. Similarly, diversity of locally endemic flora has some connection to sense of belonging (Menatti et al. 2019), but the courtyards that we studied included a broad range of species, both local and exotic.

Benefits of Including Students as Researchers

Reaching young adults to understand their unique needs and preferences can be challenging (Birch et al. 2020), and our study demonstrates the benefits of bringing students into the research process itself in order to achieve this aim. Alnusairat et al. (2022) emphasize the importance of student input in designing outdoor courtyard spaces, noting that connectivity between static spaces is an important feature to consider. Such insights, combined with evidence-based strategies from environmental psychology, can inform the creation of inclusive, restorative campus environments that prioritize health and wellbeing.

An important finding from our research was learning which survey questions most resonated with students. Detailed discussions with student researchers during the survey design stage pointed to the importance of acknowledging and respecting the lived experiences of the survey audience: in our case, these were students who are often busy, stressed, and managing anxiety within a fast-paced academic environment. Many of the student researchers expressed guilt about taking breaks away from their computers, particularly breaks spent outdoors, so we included a survey question about this potential reaction to assess how this sentiment resonated with the broader student population. Overall, our survey found that participants felt relatively neutral regarding guilt for taking breaks in contrast to Foellmer et al. (2021), which found stronger consensus for students having a ‘bad conscience’ for spending time taking breaks in campus greenspaces.

The inclusion of students as researchers offered a range of other benefits in addition to identifying unique topics. The students suggested how their peers might interpret surveys and the issues they might face while responding, refining the survey as whole to feel more relatable to their peers. As student researchers, our team members gained a better understanding of how students respond to questions and what they find challenging, such as long surveys, overly descriptive language, or poorly structured questions. When surveys are designed without consideration for the participants’ context, they risk coming across as treating participants as mere data points, rather than as individuals.

Our study also created a training opportunity for students interested in further research work as graduate students, a benefit previously noted by Adebisi (2022). According to the student researchers, their university studies suffered from a gap between theoretical learning and practical application that often left them with a feeling of incomplete accomplishment regarding their research capabilities. In contrast, engaging in research offered them a unique sense of achievement and success, aiding in the training of the next generation of academics (Russell et al. 2007). In addition, having student researchers performing observations allowed them to blend in better, supporting the robustness of their findings because visitors were less likely to feel watched.

Reflecting on our experience as a team, we believe that having students involved in research can significantly increase engagement, especially by younger populations. Young adults are often one of the hardest groups to reach, but they may feel more compelled to contribute when a study is created and distributed by someone in their peer group. A connection with the researcher can make the study feel more personal, increasing both the frequency and quality of responses. Moreover, conducting research within the familiar campus environment generated a sense of personal relevance and local impact to the student researchers. The familiarity of the study setting also provided a sense of security during site visits, because student researchers were well acquainted with the campus layout and resources.

When students share an interest in the research topic and possess knowledge of the subject, collaboration and productivity are significantly enhanced (Adebisi 2022). In our case, these factors enabled effective brainstorming, open communication during meetings, and cooperative work outside of structured sessions. The shared enthusiasm and understanding created an environment conducive to problem solving and the successful production of research outcomes. Based on our experiences, several elements are necessary to effectively engage students as researchers: a clear and well-defined objective, the opportunity to gain relevant experience, alignment with their interests, and sufficient mentorship (Russel et al. 2007). When these factors are in hand, students are more likely to contribute their full effort, leading to meaningful research experiences.

Limitations

This study was limited to one type of urban forest (courtyards adjacent to campus buildings) and took place during one time of year. This timing limits the generalizability of our results, although it should be noted that the courtyards were observed for a large portion of one of two main academic terms, occurring over midterm exams through the last week of classes. This timing also posed a limitation due to poor weather, which likely discouraged time spent in courtyards. In addition, the fact that it took place during a stressful time of the academic year may have influenced people’s ability to get out and take a break. Our survey sample of 46 respondents did not represent every academic department offered at UBC, similarly limiting generalizability. This study primarily utilized quantitative methods, supplemented by a few open-ended qualitative questions at the end of the survey. To gain a deeper understanding, more comprehensive qualitative data collection, such as interviews or focus group discussions, is recommended, similar to recommendations from Foellmer et al. (2021).

Our study did not observe or test ‘active landscapes’ where students might move or participate in sport, but inclusion of active spaces would be an important addition to future studies. Guo et al. (2023) note that dynamic activities such as exercise had a far greater restorative impact than static leisure behaviours, suggesting that campuses should prioritize spaces encouraging movement and interaction.

Future Research Directions

Our student researchers suggested additional approaches to engage young adults, specifically university students, in future studies. They suggest collaborating with diverse academic departments, particularly those focused on mental health, psychology, forestry, and environmental studies. Additionally, connecting with student-led organizations—such as student wellbeing unions, mental-health societies, and other campus-affiliated groups—could broaden the reach of the survey. Leveraging platforms such as student-society blogs, university social media accounts, and online student communities would further amplify visibility. These methods could not only reach a more diverse audience but also foster a sense of campus-community involvement, encouraging greater participation and enriching data quality.

Specific aspects of urban forests beyond the scope of the current effort would benefit from additional study. For example, future studies could test the restorativeness of urban forest spaces with local flora, particularly looking at ‘coherence’ and users’ sense of belonging. The high number of participants reporting that they used courtyards for ‘passing through’ highlights the potential importance of incidental nature exposure, which would also benefit from additional research. Length of stay was not tested in our study, but future efforts should investigate length of exposure as a factor. Because guilt over taking a break generated a heated discussion amongst the student researchers, and was also mentioned by survey respondents, this area should be considered by other teams as well.

Conclusion

Young adults, including university students, represent a population group that is experiencing challenges with poor mental health and loneliness. Diverse urban forest spaces can provide a range of related benefits, including opportunities for psychological restoration, belonging, and social interaction. Our study found that students reported finding some amount of restoration in campus courtyards, and that more biodiverse courtyards were perceived as more restorative. Our model of students as researchers benefited both the study’s robustness and the participating students themselves by offering valuable insights into effective research design and giving young adults a voice. Moving forward, campus design must adopt a participatory approach, incorporating student engagement and interdisciplinary collaboration to create natural spaces that reflect the diverse needs of their specific communities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors reported no conflicts of interest

Acknowledgements

This paper is based on a presentation given at the 5th International Conference on Urban Tree Diversity (UTD5), held in Madrid, Spain, 24–25 October 2024. The conference was organized by Arbocity, the Forestry Engineering School from the Technical University of Madrid (UPM), and the Nature Based Solutions Institute (NBSI). The authors would like to express gratitude to everyone who participated in this study, including the University of British Columbia’s Campus and Community Planning group. This research received no external funding.